by Toug Tanavin, MD, Mark Pollet, MD,

and Yochai Birnbaum, MD, FACC

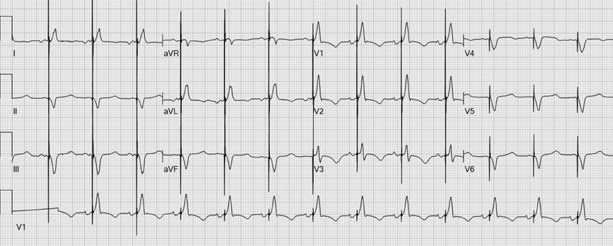

A 61-year-old man with coronary artery

disease presented with volume overload caused by medication noncompliance. His

medical history included percutaneous coronary intervention; ischemic

cardiomyopathy (left ventricular [LV] ejection fraction, <0.15); and

placement of a biventricular implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD),

model and programming unknown. Chest radiographs showed properly positioned

ventricular and right atrial leads. Figure 1 shows the patient’s

electrocardiogram (ECG) on presentation.

On the

basis of the ECG, what is the patient’s diagnosis?

A) Supraventricular

tachycardia with biventricular pacing response

B) Pacemaker-mediated

tachycardia

C) Sinus

tachycardia with normal atrioventricular delay programming

D) Antitachycardia

pacing

Answer

A) Supraventricular

tachycardia with biventricular pacing response

The ECG shows a relatively narrow QRS

complex at a ventricular rate of 100 beats/min. Notably, an rSR' configuration

in leads V1 and V2 (Fig. 2A, arrows) represents a

retrograde P wave that suggests supraventricular tachycardia—most likely

atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia, not sinus tachycardia with normal atrioventricular

delay programming.1 The ventricular pacemaker stimuli after each

intrinsic QRS complex are probably from responsive biventricular ICD pacing. After

the patient’s tachycardia resolved, we observed sinus rhythm, normal right

bundle branch configuration, and normal biventricular pacing (Fig. 2B).

|

| Fig. 2A |

|

| Fig. 2B |

When the ICD senses intrinsic activity

in one ventricle, it immediately paces the other ventricle, to better synchronize

LV contraction. However, the initially narrower QRS configuration suggests that

the LV pacing stimuli were not capturing the already depolarized ventricular

myocardium. Responsive biventricular ICD pacing is expected to produce fusion

complex morphology, as in cardiac resynchronization therapy, and indeed the

wider QRS complex after conversion to sinus rhythm indicates fusion from

His–Purkinje system depolarization with coinciding pacing stimuli.

In Figure 1, the response is not

antitachycardia pacing, because the pacing stimuli occur before the QRS complexes;

moreover, there was no burst of pacing stimuli faster than the spontaneous

rate.1 Nor is the response pacemaker-mediated tachycardia, because

the pacing stimuli occur after the QRS complexes begin.2,3 The P

waves at the end of the QRS complexes might be retrograde conduction from the

pacemaker stimulus; however, the very long subsequent PR intervals suggest another

mechanism.

References

- Issa ZF, Miller JM, Zipes DP. Clinical arrhythmology and electrophysiology: a companion to Braunwald’s heart disease. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. p. 381-410.

- Cha YM, Mulpuru SK. Cardiac resynchronization therapy programming and troubleshooting. In: Ellenbogen KA, Wilkoff BL, Kay GN, Lau CP, Auricchio A, editors. Clinical cardiac pacing, defibrillation, and resynchronization therapy. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017. p. 1090-132.

- Burri H. Pacemaker programming and troubleshooting. In: Ellenbogen KA, Wilkoff BL, Kay GN, Lau CP, Auricchio A, editors. Clinical cardiac pacing, defibrillation, and resynchronization therapy. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017. p. 1031-63.

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.