by Kelvin N.V. Bush, MD, and Gregg G. Gerasimon MD

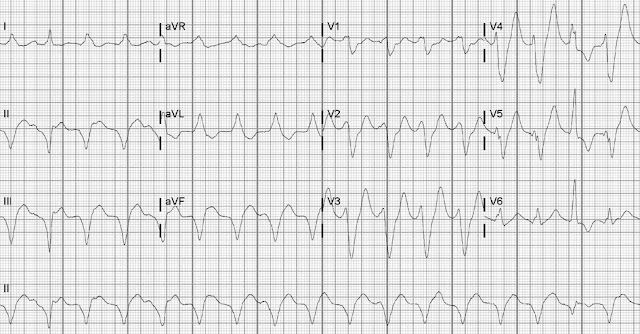

A 70-year-old man with ischemic heart disease, chronic heart failure, and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 0.25 presented with recurrent palpitations and diaphoresis. His single-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillator had recently been upgraded to a Dynagen™ X4 Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Defibrillator (Boston Scientific Corporation), and he had been taking β-blockers and amiodarone. Physical examination results were notable for hemodynamic stability, jugular venous distention, a jugular venous pressure of 12 cm H2O, and no evidence of pulmonary or hepatic congestion. The patient’s resting electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed a wide-complex rhythm (Fig. 1).

How is this wide-complex rhythm explained?

A) Ventricular tachycardia with fusion complexes

B) Supraventricular tachycardia with conduction over an accessory pathway

C) Sinus tachycardia with aberrant conduction and intermittent ectopic beats

D) Biventricular pacing rhythm with intermittent native conduction

Answer

A) Ventricular tachycardia with fusion complexes

This wide QRS rhythm may be confused with supraventricular tachycardia with aberrancy, paced rhythms, or preexcited rhythms. In our patient, however, the ECG revealed a heart rate of 104 beats/min (Fig. 2). In patients with ischemic heart disease who are taking antiarrhythmic drugs, β-blockers, or both, slower ventricular tachycardia (VT) should be considered in the diagnosis.1

A review of the Brugada criteria2 is essential. First, the ECG shows RS complexes in some precordial leads; this by itself does not exclude a diagnosis of VT. (If no precordial lead had an RS complex, it would be highly indicative of VT.) Second, the R-S interval (duration from the onset of the R wave to the nadir of the S wave) in the precordial leads is greater than 100 ms in leads V2 through V4, which strongly suggests VT as the underlying rhythm. Last, the evidence of atrioventricular dissociation—the fusion complexes (arrows)—further confirms the VT diagnosis.2,3 In addition, a P wave precedes the first fusion complex (asterisk).

During analysis of lead aVR for the initial deflection direction or duration, using a simplified aVR algorithm can aid in diagnosing VT.4 An initial R wave in lead aVR (as in our patient’s ECG) suggests VT, as does a Q-wave duration greater than 40 ms.4

Clinicians might inappropriately rely on a defibrillator to detect and terminate VT. In our patient’s device, the threshold settings were too high to detect slow VT: the antitachycardia pacing threshold was 120 beats/min and the shock threshold was 140 beats/min. Rapidly recognizing and correcting slow VT are crucial to managing and preventing a clinical decline.

References

- Leitz N, Khawaja Z, Been M. Slow ventricular tachycardia. BMJ 2008;337:a424.

- Brugada P, Brugada J, Mont L, Smeets J, Andries EW. A new approach to the differential diagnosis of a regular tachycardia with a wide QRS complex. Circulation 1991;83(5):1649-59.

- Page RL, Joglar JA, Caldwell MA, Calkins H, Conti JB, Deal BJ, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tachycardia: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67(13): e27-e115.

- Vereckei A, Duray G, Szenasi G, Altemose GT, Miller JM. New algorithm using only lead aVR for differential diagnosis of wide QRS complex tachycardia. Heart Rhythm 2008;5(1): 89-98.

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.